Autorka: Magda Z.

„Nóżki chude jak obsadki w kałamarzach czarnych butów. Sukienka z ciemnej tkaniny, jeszcze za duża, pewnie po siostrze Marysi. Na szyi podwójny sznur krótkich korali i grzywka na Marię Dąbrowską. Nic w tym dziecku nie zapowiadało urody pin-up girl, w jaką przeistoczy się w latach pięćdziesiątych” – opisywała pięcioletnią Zosię na fotografii Magdalena Grzebałkowska.

Zosia Helena przyszła na świat 25 marca 1928 r. w Dynowie jako córka Stanisławy i Jakuba Stankiewiczów. Rodzina mieszkała w jednopokojowej kamienicy z kuchnią, bez łazienki. Balkon ich domu zdobiła tabliczka sklepu z żelazem i opałem, prowadzonego przez rodziców, którzy byli aktywnymi członkami kółka różańcowego. Zosia wzrastała więc w domu skromnym i pobożnym.

Jako nastolatka walczyła z kompleksem krzywego zgryzu – który podobno uwielbiał Zdzisław – aparat na zęby założyła jednak dopiero w latach 80., mieszkając w Warszawie. Mimo niepewności siebie wyrosła na piękną i zdolną studentkę romanistyki na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim. To właśnie w czasach studenckich poznała przyszłego męża, który studiował architekturę na politechnice.

Zdzisiek pisał o niej: Córka (moja żona) studiowała wbrew ich [rodziców] woli, bo miała chyba zająć się gospodarstwem, a do studiowania przeznaczona była jej starsza siostra, która miała lepsze świadectwo szkolne. Starsza siostra zazdrościła jej urody.

Choć młody artysta nie uchodził za wylewnego, to oszalał na punkcie Zofii. Tak relacjonuje ich relację Emil Kuc, szwagier Zofii: […] czy Zosia była zakochana w Zdzisiu? [moim zdaniem] ona zakochana nie była tak, jak się zakochują młode dziewczęta, bez opamiętania […]. Natomiast Zdzisia opętało. Był tak o nią zazdrosny, że nawet magisterium jej zrobić nie pozwolił. Po swojemu ją kochał, ale był niesamowicie zaborczy pod tym względem. Zosia była dziewczyną bardzo wesołą, lubiła tańczyć, fantastycznie tańczyła, a Zdzisio nigdy z nią nie zatańczył. Był z niego chłopak temperamentny, to nie darował. Zamykali się z Zosią w łazience, innych okazji nie było.

Proza życia i zapach ciasta

Ukoronowaniem miłości Zofii i Zdzisława był ślub cywilny, który odbył się 30 kwietnia 1951 r. w Dynowie (ślub kościelny małżonkowie wzięli 11 sierpnia 1951 r. w Krakowie). Co ciekawe, znany z filmowania codziennego życia malarz nie zapewnił małżonce fotografii z ożenku – pożyczył aparat fotograficzny znajomemu, który zapomniał zabrać go do kościoła. Po zamążpójściu – jak podaje Emil Kuc – Zosia przyjechała do Zdzisława i zamieszkali na rzeszowskim osiedlu WSK w strasznych warunkach. Toaleta, kuchnia, wszystko wspólne. Nazywało się to hotelem robotniczym, ale tak naprawdę to były baraki.

W 1954 r. Zdzisław rozpoczął pracę jako inspektor budowlany w Sanoku, ale rok później zrezygnował ze stanowiska. Po jego odejściu małżonkowie przeprowadzili się do rezydencji rodziny Beksińskich, stając się nierozłącznym duetem w każdym aspekcie życia. Chociaż może się wydawać, że Zofia odgrywała drugoplanową rolę wobec męża, to wielu uważało, iż to ona była prawdziwą siłą napędową ich domostwa.

Dom Beksińskich był ostoją dla przyjaciół i znajomych, których Zofia zawsze witała z ciepłem i gościnnością. Częstowała ich kawą Marago, herbatą, winem i pysznymi pączkami od Bliklego. Piekła ciasta śliwkowe, gotowała ulubione Zdzisława pierogi z ziemniakami i śmietaną, cerowała ubrania, szydełkowała. Choć bardziej uczuciowa od męża, była małomówna. Lubiła wiatr we włosach, gdy mąż zabierał ją na wycieczki motocyklem, przyjemność sprawiało jej chodzenie do kina. Dla męża zrobiła prawo jazdy, by móc pełnić funkcję jego kierowcy.

Peszy mnie tylko, że uważa mnie Pani za taką dobrą żonę, bo ja mam jednak przekonanie, że tak nie jest. Uważam, że wielka indywidualność powinna nie być sama, ale mieć przy sobie choćby mniejszą, ale też jakąś indywidualność, a ja jestem tylko cieniem. Nie mam żadnych ciągot artystycznych, nie mam najmniejszych zdolności w jakimkolwiek kierunku, nie mam nawet zawodu, który pozwoliłby mi się samej jako tako utrzymać. Więc raczej jestem ciężarem. Moim maleńkim plusem – o ile to można tak nazwać – jest chyba tylko to, że nie jestem wymagająca. Robię, co mogę, o nic się nie upominam, pamiętają, to dobrze, nie, też dobrze, i tak życie leci. – Zofia Baczyńska

Motyl z wiatrem w skrzydłach

Dla Beksińskiego była najwspanialszą muzą – z namiętnością fotografował jej kształtne ciało, z iskrą w oku kreował portrety. Nie do końca rozumiała mroczną sztukę genialnego męża, lecz z pokorą spełniała jego artystyczne zachcianki. I wspierała Zdzisława. W grudniu 1958 r., poruszona jedną z jego wczesnych wystaw, powiedziała: Boję się żeby cię nie obśmiali za bardzo. I żeby cały Twój wkład, tak duchowy, fizyczny, jak i materialny dał jakieś owoce. Żeby cię nie rozczarowało to wszystko.

Czy poświęcała się dla Zdziśka? Jak stwierdziła przyjaciółka rodziny: Zosia była kochającą osobą. Ona wiedziała, że to jest artysta i wiedziała, dlaczego ona się poświęca [choć] […] nie użyłabym takiego słowa, bo jeśli się kogoś kocha, to się czyni to, żeby on był szczęśliwy […], tym bardziej, że Beksiński niczego od Zosi nie wymagał […]. Tak że to była jej decyzja. Była […] mu całkowicie oddana – i dla niej to było czymś naturalnym i pięknym.

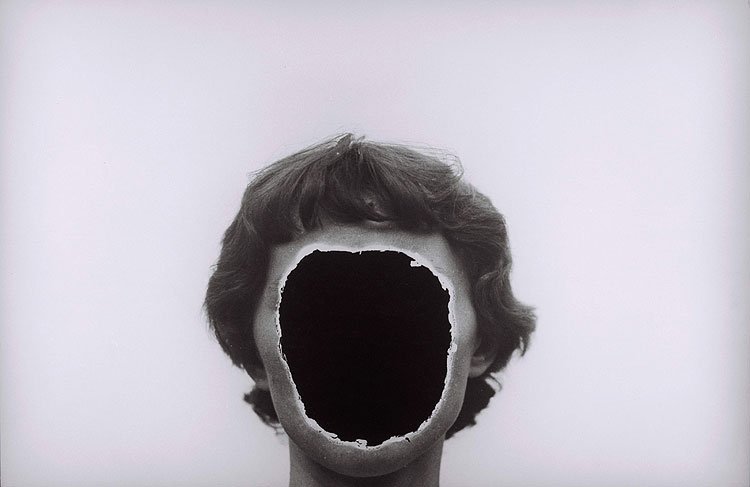

Wiele fotografii, które zrobił jej Zdzisław, przetrwało próbę czasu. Niestety, niektóre, z lat 50., zostały zniszczone przez Zofię, artysta zaś, uszanowawszy wolę żony, spalił negatywy po jej śmierci. W pamiętniku wyraził smutek z powodu utraty zdjęć, na których Zosia prezentowała się szczególnie pięknie (1953–1955). Gdy zaś ona sama stawała za aparatem, dbał o to, aby jej podpis widniał na fotografiach.

Matka – kobieta pracująca

26 listopada 1958 r. Zofia powitała na świecie syna – Tomasza Sylwestra. Ważył trzy kilogramy i sto gramów, mierzył 52 cm. Uważała Tomasza za najpiękniejsze dziecko na świecie, Zdzisław natomiast otwarcie mówił o swoim lęku i lekkiej odrazie do dzieci. Odgrywał raczej rolę kolegi niż rodzica; Tomasz, dorastając, ubolewał, że ojciec pozwalał na zbyt wiele i nigdy nie miał odwagi go zdyscyplinować.

Gdy Tomasza pochłonął mrok, Zofia stała przy nim z niezachwianą cierpliwością i empatią. Wspierała go w jego zmaganiach i podziwiała jego pracę w radiu. Zdzisław mówił o niskiej samoocenie Zofii i poczuciu porażki, które, jak sądził, Tomasz po niej odziedziczył. Jednak we wspomnieniach przyjaciół Tomka to Zofia jest zapamiętana jako wiecznie pogodna, wyrozumiała i czuła kobieta.

Nie była tylko muzą, gospodynią domu czy matką. Starała się wspierać finansowo budżet rodzinny. Warto zauważyć, że Zdzisław podejmował się różnych prac, w tym budowlanych, gdyż jego prace zaczęły się sprzedawać dopiero w 1973 r., skutkiem czego rodzina zmagała się z problemami finansowymi. Przez pewien czas Zofia Beksińska pracowała więc jako sekretarka w Liceum Pedagogicznym w Sanoku przy ul. Lipińskiego, by następnie udzielać korepetycji z języka francuskiego, który uwielbiała i w którym czytała ulubione magazyny. Pod koniec 1964 r. pobierała 20 zł za godzinę za lekcję i miała czterech uczniów. W liście do Jerzego Lewczyńskiego Zdzisław wspomniał, że wkładała wiele wysiłku w przygotowywanie się do zajęć, często pracując do późnych godzin nocnych.

Intensywny tryb życia mocno się odbił na zdrowiu Zofii. Już od początku małżeństwa chorowała na gruźlicę, a mimo wewnętrznej siły dała o sobie znać jej psychika. Lewczyński pisał: Chwilami myślałem, że Zosia coś zażywa, miewała takie stany depresyjne. Wieczorem wszystko było dobrze, a potem rano nie wstaje i cały dzień leży.

Po leczeniu w Zakopanem i Krakowie zażegnała chorobę. Jednak problemy zdrowotne z czasem wróciły w postaci tętniaka aorty. Wiedząc, że szanse na skuteczne leczenie są niewielkie, Zofia zaczęła przygotowywać męża do życia w pojedynkę. Uświadomiła sobie, że do tej pory przyziemne zadania nie zaprzątały jego uwagi i że nadszedł czas, aby mąż nauczył się radzić sobie z obowiązkami, takimi jak pranie, prace domowe i dbanie o siebie oraz o syna. Zmarła 22 września 1998 r. po 47 latach małżeństwa. Rok później do matki dołączył Tomasz, popełniając samobójstwo. Po sześciu latach od jego śmierci Zdzisław Beksiński został zamordowany w swoim mieszkaniu w Warszawie. Cała rodzina spoczęła w rodzinnym grobowcu na cmentarzu w Sanoku.